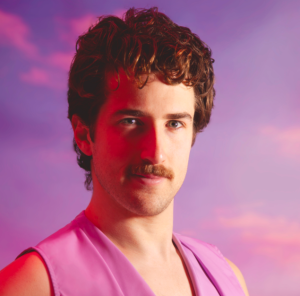

Spike Einbinder & the Rainbow Pack Walk the Walk

How the Los Espookys actor and comedian found their calling as a dog walker.

In 2020, six years into their work as a dog walker for private companies, the Brooklyn-based comedian and empath to canines Spike Einbinder launched their own independent, queer-run collective of walkers, The Rainbow Packopens in new tab. Since starting the pack, they’ve amassed a band of fellow dog walkers in different neighborhoods throughout Brooklyn, centered on an ethos of fair pay and community. We joined Einbinder on their Wednesday route to learn about the economic reality and cultural misconceptions of the invisible industry.

The Dog Walker’s Life

Contrary to the cinematic cliché, those who can’t do do not make for good dog walkers. For Einbinder and their cohort, this isn’t a gig, but a sacred calling. “Being with dogs is truly soul-nourishing to me,” they said to me, while maintaining rigid focus on our two wards for the afternoon route. Einbinder pointed out each dog’s progress to me as we walked, noting how these pandemic-era rescues were adapting to the neighborhood, and to triggering stimuli, with each walk. The common descriptor for many of their walking mates is “totally nice, totally insane. Which is like me.”

Einbinder grew up in Los Angeles, afflicted, in a crushing irony, with severe animal allergies: “I’m allergic to dogs, cats, horses, any kind of rodent, as well as feathers,” they said. The advent of hypoallergenic breeds and allergy meds allowed Einbinder to pursue their childhood adoration of dogs, but they didn’t immediately find themselves in the professional walking sphere. Einbinder worked day jobs a barista and in retail customer service — until they could take it no longer. “I was so sick of working in service with humans. It was killing me, and it was destroying my brain. I was like: If I’m going to work, can I do it with creatures that I inherently love and want to be around?”

Picking up a route for an out-of-town friend, Einbinder found instant connection. “Dogs don’t misgender me,” they said. Einbinder, who identifies as trans, is known in the Brooklyn alt-comedy milieu for their demonic, post-gender, post-human drag cabaret personas, best personified in their role as an elemental ghoul on HBO’s Los Espookys.opens in new tab But among canine company, there is no artifice. “Coming to meet these creatures, where they’re at, is something I find many people don’t do for each other, even for people who know each other.”

Freed from the “neverending toil” of their service job changed Einbinder’s idea of labor. “It’s me and a keyring, and I’m alone with dogs at Riverside Park, just communing with them. And then my job is done. I’m not opening an email after hours that I have to get stressed about.” Within years, Einbinder was a lifer, posting about their hairless dogs Fabio, Spider-man and Nelly on Instagramopens in new tab, and on walks, embracing a Road Warrior survivalistic aesthetic built for enduring any walk, any time, in any weather.

The Business

Despite the purity of relationships among the walker and their companions — “it’s something divine that will never be vanquished; you can’t break that bond” — the strenuous job is rarely well-compensated. Before the formation of the Rainbow Pack, Einbinder often found themselves exploited by middle-managers and bosses, who’d skim $5 of a $15 walk, for little more than emailing clients and assigning routes. If Einbinder would walk 25 dogs in a day, five days a week, their direct employer could claim up to $600 of their weekly profits, for little to no effort.

In the structure of dog-walking companies, the walkers are tasked with doing the impossible: covering vast swaths of territory, handling the individual needs of multiple dogs concurrently — dealing with gaps in training and any individual traumas along the way — all while employers “track and trace every interaction,” as Einbinder described it, “reducing it to a monetary amount for labor.” Einbinder told me that they would often not eat between 9am and 4pm to keep up with the demands laid upon them, “destroying my body and my capacity to think.”

The Dog Walker Community

Over the pandemic shutdown in 2020, Einbinder spoke with their fellow employees about experiences of disenfranchisement. When their employer at the time ceased operations, Einbinder broke away to start Rainbow Pack: A socialist, queer collective in which individual walkers can support one another: cover walks, share clients, “get coverage for our outsider lives; we do things that a boss would do, but we do it for each other.” Einbinder understands that for independent dog walkers, who go it alone rather than submit to vampiric corporate monoliths, “the pitfall is not having any backup.” Rainbow Pack empowers individual walkers, restoring the focus of relationships back to the clients. “I just did coverage for a walker whom I met on the street,” Einbinder said. “I was like: ‘Hey, what’s up? You’re a dog walker too? We both have they/them pronouns and were abused by former bosses? Let’s exchange numbers!”

Now, Einbinder walks fewer dogs in a day, at their own rates, allowing for longer, more considerate bonding and training time. For the many rescue dogs who found homes during the pandemic, these more attentive sessions prove key, socializing them to the animals, people, and triggers of their neighborhood. And, unlike many of the company-paid walkers who can’t afford to keep their routes for more than a few months at a time, Einbinder’s network is full of old fogies, “who have been doing it for years, who want to be there and who don’t have a boss. You want the person who is with your animal to not be stressed, and to feel sustained.”

Ethical Choices

So how do you go about finding the right dog walker, and feel good about it? Einbinder is wary of searching online: “The top results are going to be promoted with money made off of dog walkers who were exploited.” Instead, they recommend consulting with pet parents at a local park, ideally early in the morning, during off-leash hours. A thorough search, involving friends and strangers, is worth it, because once you’ve found the right walker, you’re set for life. “Dog walking is not my reputation, it’s me. It’s who I am. It’s not like I have to make you a perfect latte or you’re going to go on Yelp and write a bad review. For me, the Yelp review is to God themself if I do something fucked up with this job.”

Back-to-Work: How to Adjust

Einbinder, who works as a walker and experience-based trainer, admitted to me that many of their clients from earlier in the pandemic have come calling a year later, “when all the things I said to them about separation and anxiety training, they didn’t do.” Though Einbinder attends to each dog’s specific needs on their walks, they caution against putting too much of an onus on the walker. Working with a separate trainer is key, but more essential is ensuring consistent training on your own: “You need to find that point of connection with your dog, maintain it, strengthen it and improve upon it so that things are clear. Getting a dog is not just feeding it and having it live in your house. It’s not just the walks. It’s stimulating their minds and parsing the world out to them, especially rescues, which most of these dogs are. Training never stops.”

By the end of the walk, I felt as though I’d been trained myself: my eyes followed Einbinder’s finger commands, and I knew to halt in place and await instruction at crosswalks. The two dogs, who’d started the walks in a scattered mania now walked with focus, purpose, and ease. I couldn’t believe Einbinder’s intensity, let alone their stamina. But for them, it’s not a job or a distraction. It’s destiny. “I have grown as a person by helping dogs grow. They’re not objects, they’re not babies. They’re dogs. We need to respect them and support them, just like they support us. And we need to support the people who handle them, and who you employ.”